NOBODY likes home economics. For most people, the phrase evokes bland food, bad sewing and self-righteous fussiness.

NOBODY likes home economics. For most people, the phrase evokes bland food, bad sewing and self-righteous fussiness.

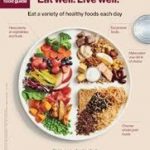

But home economics is more than a 1950s teacher in cat’s-eye glasses showing her female students how to make a white sauce. Reviving the program, and its original premises — that producing good, nutritious food is profoundly important, that it takes study and practice, and that it can and should be taught through the public school system — could help us in the fight against obesity and chronic disease today.

The home economics movement was founded on the belief that housework and food preparation were important subjects that should be studied scientifically. The first classes occurred in the agricultural and technical colleges that were built from the proceeds of federal land grants in the 1860s. By the early 20th century, and increasingly after the passage of federal legislation like the 1917 Smith-Hughes Act, which provided support for the training of teachers in home economics, there were classes in elementary, middle and high schools across the country. When universities excluded women from most departments, home economics was a back door into higher education. Once there, women worked hard to make the case that “domestic science” was in fact a scientific discipline, linked to chemistry, biology and bacteriology.

Read the rest of this column at the New York Times.